Preparing Necessary Chemicals

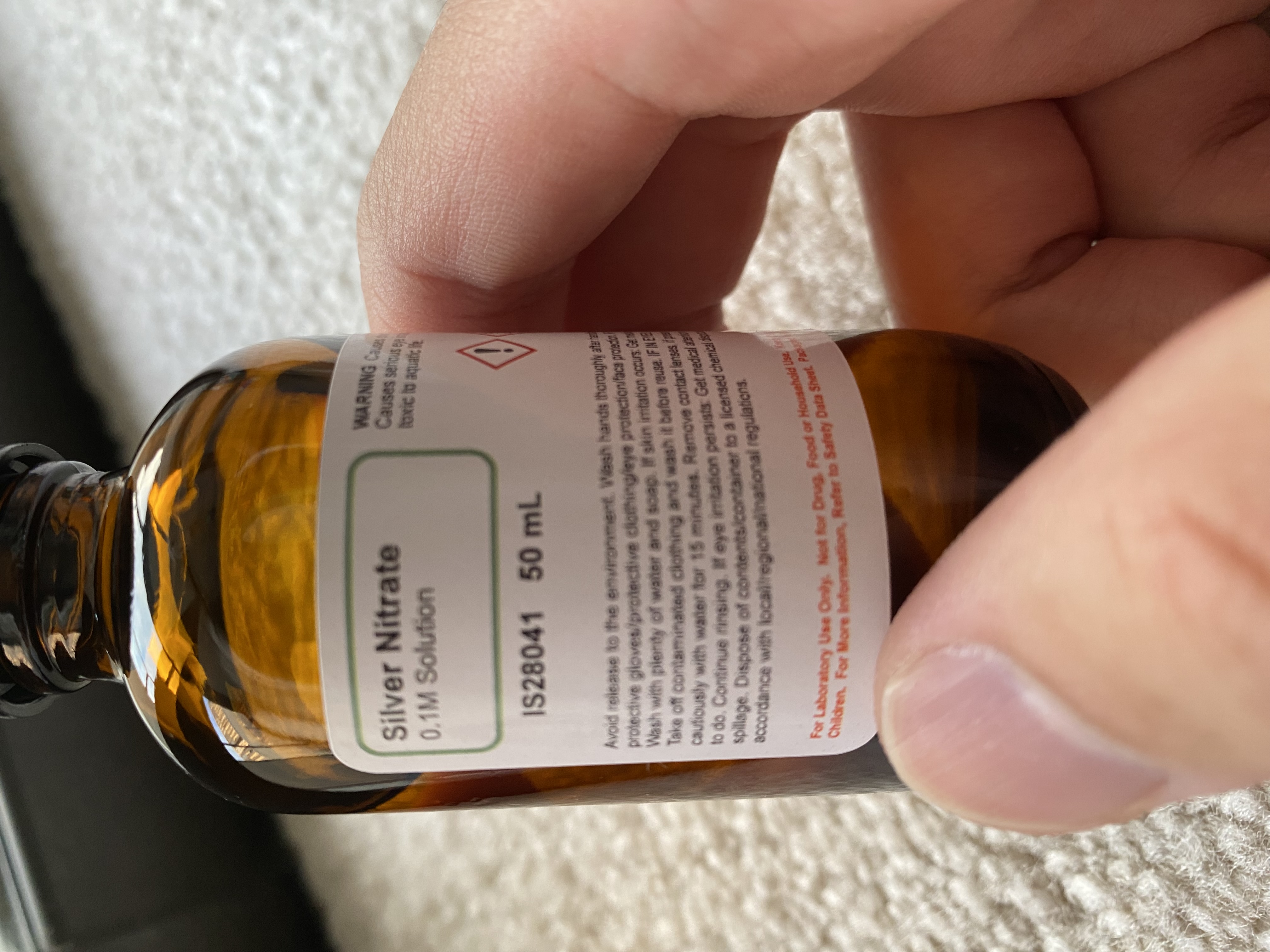

Silver Nitrate Solution

I purchased silver nitrate (AgNO3) independently since it was not available in the school’s chemical inventory. Silver nitrate is a controlled reagent due to its cost and light sensitivity, so obtaining it required ordering from a chemical supplier. The solution had to be stored in an amber bottle to prevent photodecomposition, as silver nitrate is highly light-sensitive and degrades when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, forming metallic silver precipitates that would compromise the solution’s concentration. Figure 5 shows the 0.1 M silver nitrate solution stored in a light-protective container.

Other Reagent Acquisition from Chemical Storage

0.1 M Sodium hydroxide (NaOH):

Obtained from base stock solutions. Sodium hydroxide is hygroscopic (absorbs moisture from the air), so I verified the solution’s concentration and checked for carbonate contamination,

which occurs when NaOH reacts with atmospheric CO2. If the stock solution had shown signs of degradation, I would have prepared a fresh solution from solid NaOH pellets and standardized it;

however, the available stock was suitable.

Ammonia Solution (NH3/NH4OH):

Concentrated aqueous ammonia (typically 28–30% NH3) was obtained from chemical storage. This solution is volatile and has a pungent odor,

so all handling was conducted in a fume hood. For Tollens’ reagent preparation, the solution was diluted to the appropriate concentration or used directly depending on protocol requirements.

Dextrose (Glucose) Solution:

Solid dextrose (D-glucose, C6H12O6) was retrieved from organic chemical storage, and a fresh solution was prepared by dissolving a measured mass in distilled water.

Glucose acts as the reducing agent in the silver mirror reaction, so solution freshness was important; old glucose solutions can partially oxidize or undergo bacterial contamination, reducing their effectiveness.

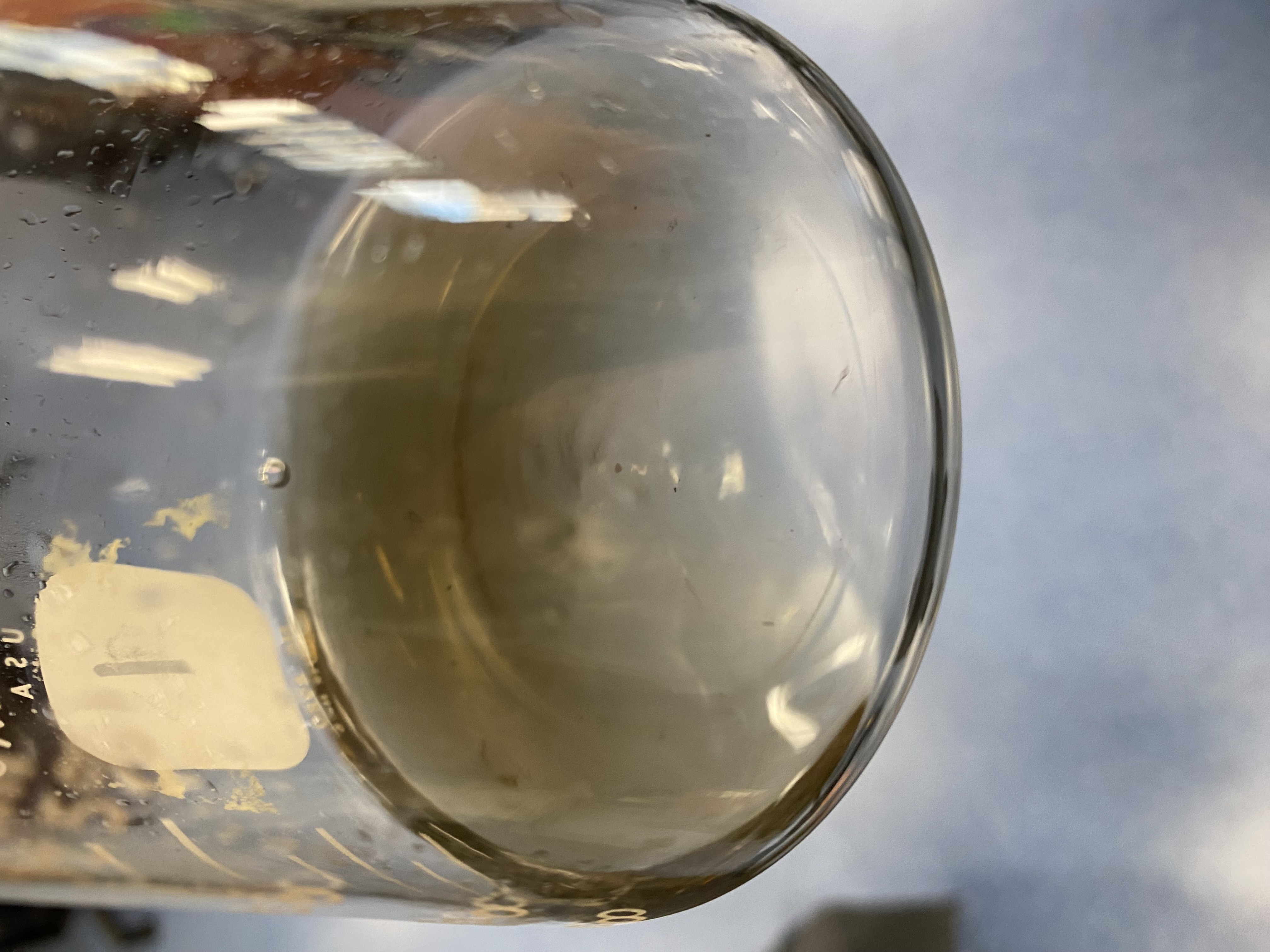

Initial Attempt and Troubleshooting

Our first attempt at the silver mirror reaction failed to produce the desired results. Instead of forming a reflective silver coating, a brown precipitate formed, as shown in Figure 6. This outcome indicated that silver ions were reducing too quickly or unevenly, forming colloidal silver or silver oxide rather than depositing as a smooth metallic film on the glass surface.

To troubleshoot this issue, we identified several potential problems with our initial conditions. The reaction temperature may have been too low, slowing reduction kinetics and preventing uniform film formation. Additionally, the silver nitrate concentration may have been insufficient to provide an adequate supply of Ag+ ions for mirror deposition. We adjusted the following reaction conditions for our second attempt:

- Temperature control: Implemented a warm water bath to maintain a consistent elevated temperature, promoting controlled reduction kinetics.

- Silver nitrate concentration: Increased AgNO3 concentration to provide greater Ag+ availability.

- Scale: Conducted the experiment with a larger team to ensure more careful monitoring and execution of each step.

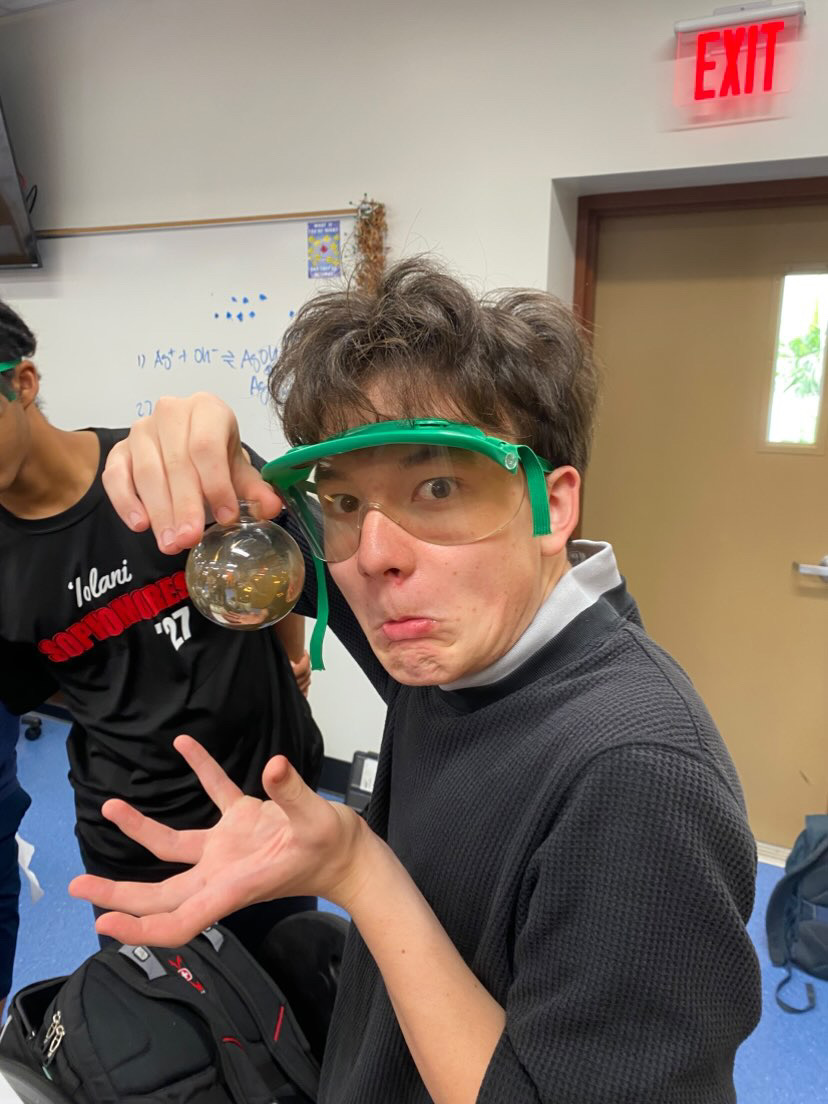

Successful Silver Mirror Formation

We repeated the experiment several weeks later while incorporating these adjustments. With the heated water bath maintaining an optimal reaction temperature and a higher AgNO3 concentration, the results improved significantly. As shown in Figure 7, a clear and reflective silver mirror formed successfully on the glass surface. The uniform metallic coating demonstrated that the controlled conditions allowed for proper reduction of Ag+ ions to metallic silver (Ag), which deposited evenly on the glass rather than precipitating as brown colloidal particles.

The success of this second attempt confirmed that temperature control and adequate reagent concentration are critical parameters for the silver mirror reaction. The warm water bath ensured that the reduction proceeded at an optimal rate (fast enough to deposit silver onto the glass surface) but controlled enough to prevent rapid precipitation in solution. The increased concentration of silver nitrate provided sufficient Ag+ ions to form a complete reflective coating rather than a scattered precipitate.